Can SARS-Cov2 mass testing help to combat the pandemic? The case of Italy

I'm working on this post a while after the first round of corona mass testing was held in two Austrian states, Tyrol and Vorralberg - with not really surprisingly low commitment of the society. For the neighbor Italian province South Tyrol, it's more than two weeks since the highly frequented mass testing campaign: enough to carefully say if it has helped the region to combat the pandemics. In my last post, I tried, quite naively, to assess the efficacy of the test by simply comparing incidences in two neighboring Italian regions. Now it's time to do it in a more systematic way by investigating the development of the pandemic in Italy as a whole, it's regions and particular South Tyrolean municipalities.

At this point I'd like to thank my data sources: Wikipedia, South Tyrolean health authorities, ISTAT and the developers of Tyrolean municipality dashboard for sharing the incidence and mortality figures and mass test results with every curious citizen of the Earth. A really great job!!! As usual, the analysis scripts can be found here.

A whole country perspective: the South Tyrolean way is highly effective

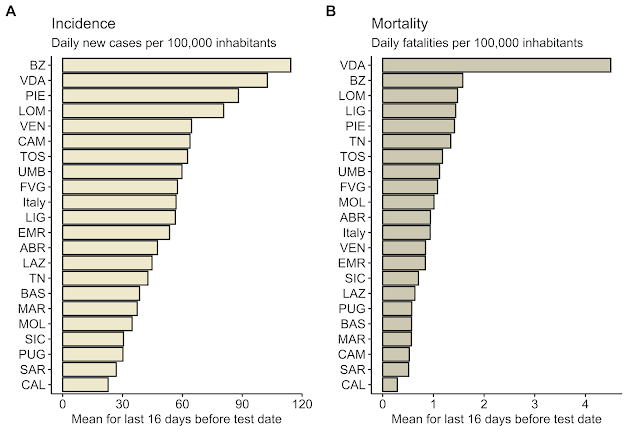

Without any doubt, Italy is one of the European countries most severely confronted with the pandemic, both in terms of mortality and economic aftermath. During the second wave of the outbreak raging in fall/winter 2020, northern regions, including South Tyrol (BZ), Aosta Valley (VDA), Lombardy (LOM) and Piemonte (PIE) rank at the top of the incidence and mortality (Graphic 1). At the peak of the wave, mid-November, most of the country was claimed 'red-zone' with stringent lockdown policies, including restricted mobility of the citizens and social distancing.

Graphic 1. Mean incidence and mortality scaled to 100,000 inhabitants for Italian regions for 16 days before the day of South Tyrolean mass test (2020-11-22, South Tyrol: BZ). Sources: outbreak data Wikipedia, population numbers ISTAT.

These quite dramatic figures in the province probably motivated the decision of South Tyrolean authorities to try a quite unusual measure to combat the outbreak: mass testing of the whole population and isolating positive cases, even if not symptomatic. The campaign took place on 20th, 21th and 22th November and, in terms of popularity, turned out to be a success. In total, almost 65% eligible inhabitants participated. Based on this high frequency, the local lockdown policy was loosened and the immediate reduction of COVID-19 incidence proclaimed a proof of efficacy of the mass test.

To test, whether this may be the case, I had a look at the pandemic figures: incidence (Graphic 2) and mortality (Graphic 3) scaled to the population for South Tyrol and the remaining country 16 days before and after the test. Why 16 days? The answer is quite simple: I'm writing the post 16 days after the test and sought to compare two equal and as long as possible time intervals around the test. To be honest in comparing the figures, which are way higher for the northern province than in the remaining country, I also included relative incidence and mortality calculated as a ratio of the daily number and the mean in the last 16 days before the mass test. As you may notice, the data show a strong weekly fluctuation - which was included as a confounder in my analyses.

Graphic 2. Daily incidence scaled to 100,000 inhabitants and daily relative incidence (ratio of daily incidence to the mean incidence for 16 days before the mass test date) in South Tyrol (BZ) and the remaining country 16 days before and after the South Tyrolean mass test. Trend lines fitted by LOESS. Data were analyzed by linear modeling with fixed effect of the time interval (after/before the test) and correction for the weekly fluctuation of the figures (random effect of day week). Modeling results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR method). Sources: outbreak data Wikipedia, population numbers ISTAT.

Let's have a look at the incidence first: it's falling not only in South Tyrol but also in the rest of Italy in the period around the test, most likely as a result of containment measures issued by the central government. However, the new case counts are plummeting even steeper in South Tyrol! This drop is significantly greater in terms of raw (extra minus 42 cases in the province) and relative incidence (extra minus 19% cases in South Tyrol compared with Italy).

Graphic 3. Daily mortality scaled to 100,000 inhabitants and daily relative mortality (ratio of daily mortality to the mean mortality for 16 days before the mass test date) in South Tyrol (BZ) and the remaining country 16 days before and after the South Tyrolean mass test. Trend lines fitted by LOESS. Data were analyzed by linear modeling with fixed effect of the time interval (after/before the test) and correction for the weekly fluctuation of the figures (random effect of day week). Modeling results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR method). Sources: outbreak data Wikipedia, population numbers ISTAT.

Mortality, undoubtedly the most crucial parameter during the outbreak, does not seem to change substantially before and after the mass test. Well, this may be a question of time - a drop in this parameter follows the daily incidence with a few week lap. Nevertheless, there's a tendency towards less fatalities in South Tyrol after the test (extra minus 34% as compared with the remaining country).

For politicians and common citizens of the northern province, the COVID-19 figures riding down faster than a country average are certainly a reason to tap themselves on the shoulder and claim the mass test strategy effective. Well, the story is getting more perplexed, if we eye at a bit deeper level...

Some Italian regions are as efficient as South Tyrol at suppressing SARS-Cov2 incidence

As you certainly noticed, during the first COVID-19 wave in Italy, regions of the country were affected by the outbreak to a various extent, with Lombardy and Bergamo province being particularly heavily struck. As we saw above, the disease incidence and mortality vary greatly between the regions during the second wave as well (Graphic 1). Those net epidemiology figures are in this case not only an effect of disease clusters but also of local preventive measures issued by the region's authorities in addition to the central government. Such measures may work better or worse at the local level: let's investigate them now and compare with the effects of South Tyrolean containment management with other Italian regions.

When split into the regions, the drop in daily incidence scaled to the population after the test looks particularly impressive in two northern autonomous regions: South Tyrol and Aosta Valley (Graphic 4A) with a highly significant reduction of roughly 60 cases for 100,000 inhabitants after the test date. However, we have to bear in mind, that those two demonstrated the highest COVID-19 figures at the day of the Tyrolean mass test. When we have a look at the relative reduction of incidence (Graphic 4B), there's a number of other regions which have reached the same or push down the incidence even further: Tuscany (TOS), Liguria (LIG), Umbria (UMB) and Lombardy (LOM) with an approximate decrease of new cases by 50% or more within the last month.

Graphic 4. Daily incidence scaled to 100,000 inhabitants and daily relative

incidence (ratio of daily incidence to the mean incidence for 16 days

before the mass test date) in Italian regions (South Tyrol: BZ) and the entire country 16 days before and after the South Tyrolean mass test were compared. Data were analyzed by linear modeling with fixed effect of the time

interval (after/before the test) and correction for the weekly

fluctuation of the figures (random effect of day week) for each region separately. Modeling results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR method). Upper plots: estimated incidence change after vs before the test date plotted against the significance. Lower plots: estimated incidence change after vs before the test date with 95% confidence intervals. Sources:

outbreak data Wikipedia, population numbers ISTAT.

Note, none of them have ever decided to perform a SARS-Cov2 test of the whole population! Hence, it may not be the mass test, which makes your state's containment strategy particularly successful. In other words, one can speculate if the mass test could really substantially add to the anyway efficient South Tyrolean policy and if the impressive drop in incidence would have happen anyway... It seems to be all about how well you can motivate your state's citizens to reduce the contacts, keep the distance and how well you track and isolate the disease clusters.

Graphic 5. Daily mortality scaled to 100,000 inhabitants and daily relative

mortality (ratio of daily mortality to the mean mortality for 16 days

before the mass test date) in Italian regions (South Tyrol: BZ) and the entire country 16 days before and after the South Tyrolean mass test were compared. Data were analyzed by linear modeling with fixed effect of the time

interval (after/before the test) and correction for the weekly

fluctuation of the figures (random effect of day week) for each region separately. Modeling

results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR

method). Upper plots: estimated mortality change after vs before the

test date plotted against the significance. Lower plots: estimated mortality change after vs before the test date with 95% confidence intervals. Sources:

outbreak data Wikipedia, population numbers ISTAT.

As we saw before, the decreased incidence still haven't translated into less COVID-19 fatalities in the regions with the exception of Aosta Valley (VDA) (Graphic 5). In fact, it continuous to rise in the entire country, even in the regions with strong decreases in incidence like Piemonte (PIE). This may have multiple reasons - and I may touch upon them in another post!

COV-figures and percent positive tests in South Tyrolean communes: did it work? can I trust the mass test results?

In contrary to the currently running Austrian mass test campaign, the South Tyrolean test results were made available to everybody - and not only for the entire province but also for single municipalities. Similarly, infection counts for each commune of the province are made public as well, which makes my analysis even more interesting. Chapeau for transparency - even if it exposes you to the critic, it's a cornerstone of modern democracy!

Before we set off with the local South Tyrolean data, I'll make three straight forward assumptions concerning efficacy and reliability of the mass test:

- if the mass test proves effective at reducing SARS-Cov2 incidence in the entire province, it has to be effective at the level of single province's municipalities

- the effect of the mass test is supposed to be bigger in the municipalities with high testing frequency than in those where the test was less popular

- the mass test results, if reliable, are expected to reflect disease activity/incidence in single municipalities

In the entire province, roughly 65% target population was tested for SARS-Cov2 with rapid antigen tests. However, the testing frequency varied from 49% in Taufers/Turbe to over 79% in Kurtinig/Cortina. If our first and second assumption is true, we should observe a reduced incidence after the test in each commune, but the effect should be significantly greater in those with a high percent of population tested. One sentence of explanation: cause many of the communes in the state are tiny and hence experience single SARS-Cov2 cases, calculating daily incidences and scaling to the population would give quite strange numbers. Instead, I'll stick to cumulative incidences, i. e. sums of case within 16 or 30 days before and after the mass test.

As shown in Graphic 6, the 16 day cumulative incidence dropped after the test in the huge majority of the municipalities (110 out of 116 communes). In hard figures: the cumulative incidence plummeted from an average 1400 new cases for 100,000 inhabitants by 830 in the communes with over 65% testing frequency. Interestingly, the effect of the mass testing was at least equally strong in the low frequency ones! (extra minus 160 new cases, not significant).

Graphic 6. Cumulative 16-day SARS-Cov2 incidence in South Tyrolean communes with high and low testing frequency 16 days before and after the mass test. Data were analyzed by linear modeling

with fixed effects of the time interval (after/before the test) and testing frequency (below/over 65% population tested) and the random effect of each municipality. Modeling results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR method). Plots: points represent single municipalities, lines connect numbers belonging to the same commune. Source: commune COV-19 dashboard, testing frequency from province's health authorities.

with fixed effects of the time interval (after/before the test) and testing frequency (below/over 65% population tested) and the random effect of each municipality. Modeling results were corrected for multiple comparisons (Benjamini/Hochberg FDR method). Plots: points represent single municipalities, lines connect numbers belonging to the same commune. Source: commune COV-19 dashboard, testing frequency from province's health authorities.

Following the counts in the extreme communes: highly-tested Kurtinig/Cortina experienced a reduction of 16-day incidence for 100,000 people by 1277 cases and the same figure for poorly-tested Taufers/Turbe dived by dramatic 1752 cases! So, interestingly enough, the mass test seems to work even if not frequented by the local community. Or, more likely, its effects are surmounted by 'traditional' and less spectacular epidemiological measures like contact reduction, hand hygiene, contact tracing and quarantine!

Graphic 7. Correlation of fraction of positive mass test results with cumulative, population-scaled 16- and 30 day incidence before the test day in South Tyrolean communes stratified by mass test frequency. Each point represents a single commune, blue lines show LOESS trends. Data were analyzed with Pearson's correlation for high- and low test frequency communes separately and with linear modeling with fixed effect of cumulative incidence and random effect of testing frequency. Source: commune COV-19 dashboard, testing frequency and results from province's health authorities.

Our last assumption states that if the test proves highly specific and sensitive, the count of positive results should be higher in a commune with large SARS-Cov2 incidence and low in one with less disease activity - it's expected that the percent of positive tests correlates with the incidence before the campaign at the level of single municipalities. As shown in Graphic 7, the percent of positive mass test results does not really follow the cumulative incidence in the province's communes in the 16 and 30 days before the mass test. The same holds true, if we split the municipalities into high- and low-tested ones. Curiously, the highest test positivity tended to be found in the communes with low-to-middle incidence! Whatever the reason, it could not be stated that the mass test outcome reflects the infection prevalence in the populations of Tyrolean communes - and, hence, its accuracy has to be questioned.

Summary: there are better SARS-Cov2 containment measures than mass testing

In my previous post, I demonstrated how the mass testing strategy may work and which results are expected, given a relatively high SARS-Cov2 prevalence, like those in Austria at the peak of the fall/winter wave. Meanwhile, the daily count of new infections in Austria and most European countries goes down thanks to stringent lockdown policies, the traditional 'test and trace' strategy and, most importantly, sensibility of common citizens, who, in a great majority, obey the rules of social distancing and reduced their contacts.

In case of South Tyrol and Italy, I couldn't find any compelling evidence for efficacy of the mass testing strategy. In particular:

- SARS-Cov2 incidence but not mortality drops in South Tyrol at a significantly faster rate than in the remaining country

- curiously, similar and even greater decrease of new case counts could be observed in other Italian provinces, including strongly affected Lombardy or Aosta Valley, which didn't decided to test the whole state's population

- within South Tyrol, the apparent effect of the mass test on incidence is the same or slightly greater in low test frequency communes than in highly tested ones

- at the single commune level, the figure of positive mass test results does not correlate with the SARS-Cov2 incidence before the test, indicating that the results are substantially influenced by false negatives and false positives

Comments

Post a Comment