Pandemic, containment management or COVID-19: what is more dangerous for mental health?

It's again a while since the last post and almost two years of pandemic. Sadly said, a misery which would have been already over, at least in the first world, provided a better vaccination readiness of the US and European societies and more courageous political decisions. Frankly speaking, none of us is the same kind of a woman or men as before the SARS-CoV-2 crisis. Besides the real threats to our somatic health, there's another facet of human well being less prominently addressed by media news and scientific publications: mental health. Fear, paranoid feeling of being locked up, overwhelming concerns about own and family health, household finances, kids without school, lost jobs... This all has been burdening us and now seems to be somehow over but not completely. Could we measure this impact on mental integrity? Could we find out the causes? Is there a way to identify people at risk of mental health deterioration early on and help them? The team of 'Health after COVID-19 in Tyrol', I'm proud to collaborate with, asked these and many other questions. We're doing our best to deliver the answers like in our latest preprint and an open-science dashboard which allows you to play around with our data and find interesting associations between demographics, social, economy and clinical status of COVID-19 convalescents and mental health.

Both COVID-19 and pandemic-related stress affect mental health and quality of life

Quite unfortunately, the pandemic denialists and vaccination critics gain at least the same amount of public interest as efforts of thousands of experts, much more study volunteers, deeply committed health-care professionals and, last but not least, by the millions of vaccinated citizens, whose immune systems allow us to fight of the virus. If not Austrian, you may have not noticed, that the denialist scene driven by alternative facts and hate towards rationality even grounded a political party which may manage once to enter the parliament of the alpine republic. But there's one argument put forward in almost every clash with this society: the way we manage the pandemic makes us ill. Well, it's true, at least for some vulnerable groups of our community.

In our latest sub-study 'Mental Health after COVID-19 in Tyrol', we quantified extents of anxiety, depression, stress and deteriorating quality of life in patients recovering from 'ambulatory' (i.e. non-hospitalized) COVID-19 recruited independently in the state of Tyrol/Austria and the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol/Alto Adige in Italy. In sum we analyzed a quite broad palette of demographics, social, economic data along with the medical history, COVID-19 course and recovery trajectory for over 2000 volunteers.

Once you launch our dashboard or have a look in the paper you may be shocked by finding out that approximately 20% of the study cohorts had clinically relevant signs of depression or anxiety. In fact, this is quite comparable to the general non-COVID-19 population gauged by very similar tools during the pandemic and, notably, more than before the crisis (see the paper by Pieh an colleagues). Is hence the pandemic setup more disastrous to our psyche than COVID-19, at least in its 'mild' form? As a COVID-19 denialist you may draw this tempting conclusion. As a scientist, you tend to question such seemingly simple findings.

Figure 1. The most important factors affecting the combined mental-health assessment, quality of life scoring, depression and anxiety in the study collectives identified by machine learning ad principal component analysis. For non-data-freaks: the arrow length corresponds to the impact on the combined mental integrity scoring. 3Q, 4Q: 3rd and 4th score quartile/high and extreme high scoring, persist.: persistent, prol.: prolonged, SIF: severe illness feeling

Skipping technical details, we build models describing quality of life, self-perceived mental health rating, depression and anxiety based on somehow 140 demographic (age, job, housing conditions and more) and clinical parameters (like comorbidity, drugs) of our participants, including those referring to the course of acute COVID, symptoms and recovery. Next, we measured the impact of each variable on the performance of such models - or their importance for the mental health rating, if you wish (Figure 1). If you're not familiar with such analyses - the length and direction of the vector in the plot is essential as it represents the strength and direction of the parameter's impact on the mental health. As you may appreciate in Figure 1, psycho-social stress has by far the greatest impact on the mental integrity after COVID-19. Especially in the Austrian cohort, disease-related factors such as symptoms, persistent complaints or long COVID stay far behind.

It has to be noted, that we gauged a particular type of stress in our study, so called 'psychosocial stress' with a series of questions concerning tensions at the working place, in the relationship, care duties. Hence, you may imagine that such stress is primarily triggered by the way the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is managed: by home office with kids on one's lap, breakdown of the social life, closed schools and so on. Does it mean that COVID-19 and it's symptoms even if lasting for weeks or months does is irrelevant to the psyche? Or one experiences more stress because of the stressing pandemic canvas combined with own symptoms?

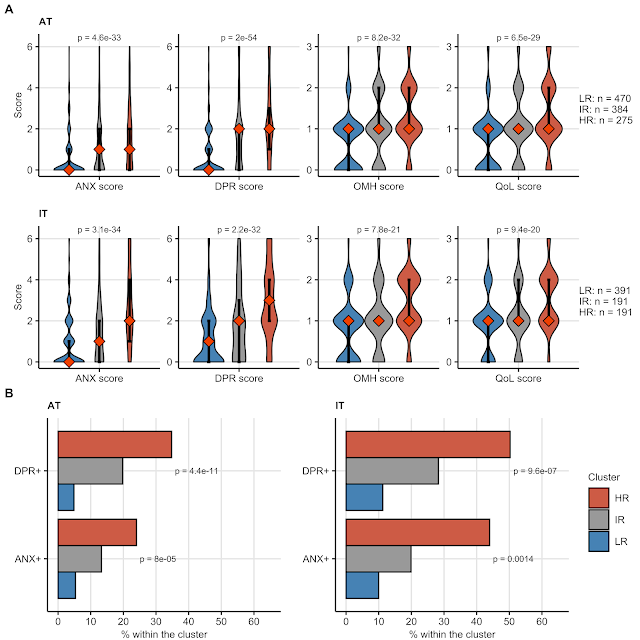

To address that we searched applied an AI algorithm with a chic name 'self-organizing map' (SOM) to classify our participants in an unsupervised manner, i.e. not knowing their mental health rating, just based on the most impactful disease related, demographic and stress variables (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Clusters of the study participants classified with the SOM procedure by the top 10 most important demographic, clinical and stress parameters identified in Figure 1. 3Q, 4Q: 3rd and 4th score quartile/high and extreme high scoring, persist.: persistent, prol.: prolonged, SIF: severe illness feeling

This procedure returned three clusters of participants, termed by us 'low risk' (LR), 'intermediate risk' (IR) and 'high risk' (HR). By simple eye-balling of their heat map representation in Figure 2, you can easily discover an interesting pattern: IR and HR clusters are primarily defined by the disease factors which overlap with high stress levels only to some extend. Specifically, concentration and memory deficits, high burden of acute and persistent symptoms determine the patterns seen in the study cohorts. Next, we took a closer look at depression, anxiety, self-perceived mental health and quality of life rating within the LR, IR and HR clusters (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mental health and quality of life measures within the clusters defined by stress, demographic and disease-related factors in Figure 2. (A) scoring presented as violin plots, differences in scoring compared with Kruskal-Wallis test, (B) frequency of clinically relevant depression and anxiety (3 points or mode) compared between the clusters with Chi-squared test. ANX: anxiety, DRP: depression, OMH: self-perceived overall mental health deterioration, QoL: quality of life loss. HR, IR, LR: high, intermediate and low-risk cluster.

Please note: the higher the score, the worse the outcome. With this in mind, you can easily discern substantial differences in the mental health quality between the clusters. Given that with 3 points or more, one should actually consider professional psychological or psychiatric support, the HR and IR clusters suffering from pestering acute and long-lasting COVID-19 symptoms are at particular risk of a serious de-novo mental disorder or an aggravation of the per-existing one. Conversely, the largest low-risk LR cluster with more or less complete somatic recovery from COVID-19 has low chances (even lower than the general non-COVID-19 population!) of developing a mental condition even when exposed to the external pandemic stress. It's quite conceivable: when you have to manage your hard working day, teach your school kids at home, take care of elderly and concomitantly struggle with post-COVID-19 memory lapses, shortness of breath and brain fog, at some point you are at limit of your mental stamina.

Perspective

Our work indicates that both COVID-19 in its 'mild' form and the pandemic management may lead to a profound deterioration of mental health. Or in other words, the incompleteness of bodily COVID-19 convalescence makes one prone to a mental disorder in this stressing time of SARS-CoV-2 crisis. Additionally, our data uncover the mental side of long COVID and underline the need of robust identification of mental disorder-prone convalescents who require psychological support. Hence, the word is not as simple as claimed by those that the there's no SARS-CoV-2, no need for containment management and ivermectin may save the world. We need to sustainably stop the pathogen spread, especially now when the situation in Austria slips out of control not only to save lives but also to save minds. And last but not least, we have the most powerful tool to achieve that - without lockdowns, social life shutdown and rampage to the economics - the vaccination. Go for it!

Comments

Post a Comment